The thyroid function and its importance

The thyroid gland plays a crucial role in controlling the body's metabolic rate, which corresponds to the speed at which our cells consume energy. Therefore, any dysfunction of the thyroid can be a significant issue, as it can lead to a lack of energy necessary for various physiological processes, such as the immune system, fertility or cholesterol metabolism. (Sources: 1, 2, 3)

Serious issues regarding the thyroid are thought to be rare. However, the prevalence of "subclinical" hypothyroidism is controversial. Hashimoto's disease, an autoimmune disease that involves the thyroid (primarily in women) and features antibodies against substances involved in thyroid hormone production, could affect 1 in 20 people.

The thyroid system is, like most body’s processes, quite complex. It involves multiple organs. It starts in the brain where the hypothalamus produces an hormone called TRH, which then leads to the release of the TSH hormone by the pituitary gland. The TSH then stimulates the production, in the thyroid directly this time, of thyroid hormones referred to as T4 and T3 (containing respectively 4 and 3 iodine atoms). The latter hormone is the most important one as it is the most active regarding the control of the metabolism. The thyroid produces some T3 and much more T4 (following a ratio of about 1 to 13).

The thyroid system also involves the liver where T4 molecules are converted to T3 by means of the removal of an iodine atome, via enzymes called deiodinases. Thus, liver health is also important for this system to work well.

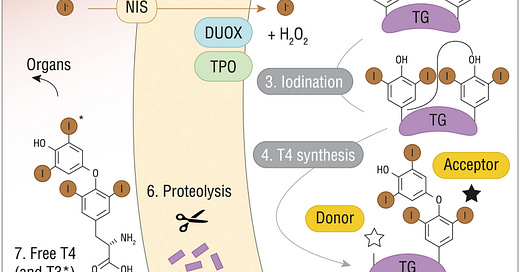

In the thyroid, the synthesis of T4 and T3 involves a series of steps (e.g. uptake of iodine and biochemical reactions involving enzymes) that can fail to do their jobs properly.

Thyroid hormones synthesis - Credits : https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.662582

Iodine is first transported into the thyroid with help of the Sodium/iodide symporter (referred to as NIS). Then, iodine is integrated in a molecule called thyroglobulin during a process called iodine organification. This process requires an enzyme called thyroid peroxidase (aka TPO, a target of antibodies in Hashimoto’s disease) which chemically prepares iodine to be integrated into thyroglobulin, a means of storing T4 and T3 hormones in the thyroid before their secretion into the blood.

These different steps are generally stimulated by the presence of the TSH hormone. In the case of a dysfunction in some of them, the thyroid won’t respond to TSH accordingly, as it can’t produce T4 and T3 in sufficient quantities, which would induce as a reaction an increase of blood TSH levels, as there exists a feedback loop between T3 levels and TSH secretion in the blood.

In addition to iodine, selenium is an important requirement of the thyroid function as it allows some fundamental enzymes to work: deiodinases contain it, but also glutathione peroxidases which protect the thyroid gland from oxidative stress. Supplementation with selenium has been shown to reverse the levels of antibodies associated with Hashimoto’s disease and to help lowering TSH.

In conclusion, the thyroid system can fail from different factors:

A deficiency in a susbtance involved in the thyroid system (iodine, selenium, inositol, etc);

Some process that is not happening how it should as a signal is not propagated correctly;

It hasn’t been addressed already, but the thyroid hormones’ effects are dependent on energy supply. Like a gas pedal, it can’t work if there is no gas.

After this introduction, we will review the (not necessarily exhaustive) connections that seem to exist between the thyroid system and water homeostasis.

First, let’s begin by studying a theoretical complementarity between the effects of the TSH hormone on the thyroid and hyperosmolarity, a state of high concentration of solutes in the blood.

TSH and hyperosmolarity complementarity

In the following study, we learn that the CREB3L1 transcription factor constitutes a link in the signaling chain between TSH and some of its effects on the thyroid gland. These effects include the uptake of iodide by the thyroid:

Here, we analyzed the role of CREB3L1 as a TSH-dependent transcriptional regulator of the expression of the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS), a major thyroid protein that mediates iodide uptake. […]

Taken together, our findings highlight the role of CREB3L1 in maintaining the homeostasis of thyroid follicular cells, regulating the adaptation of the secretory pathway as well as the synthesis of thyroid-specific proteins in response to TSH stimulation. […]

Our findings argue in favor of the notion that, under physiological conditions, CREB3L1 may contribute to thyroid cell differentiation promoting the production of thyroid hormones. […]

Participation of CREB3L1 in a hormone synthetic pathway has been also reported in pituitary gland where CREB3L1 not only regulates transcription of the gene coding for antidiuretic hormone arginine vasopressin (AVP), but also its processing via increased Pcsk1 expression, revealing its role as a key molecular component of AVP biosynthesis.

We also learn that CREB3L1 is involved in the synthesis of vasopressin (also known as AVP in the literature), an antidiuretic hormone. The connection between CREB3L1 and the effect of hyperosmolarity on vasopressin synthesis and secretion is developed in this publication:

Clearly, TonEBP is the upstream transcription factor for hypothalamic AVP gene transcription, and it contributes to hyperosmolality-dependent AVP synthesis. […]

These results suggest that TonEBP may be necessary, but not sufficient by itself, for dehydration-dependent AVP gene expression in the PVN/SON. This also suggests an involvement of other signaling(s), in addition to TonEBP, in such a case. In support of this view, recent investigations have demonstrated that cAMP responsive element-binding protein-3 like-1 (CREB3L1) and caprin-2 are distributed in the PVN/SON, possess an ability to bind directly to promoter and mRNA regions of AVP, respectively, and play a role in AVP-mediated and osmotic stress-dependent physiological adaptations.

NFAT5, also known as TonEBP in the scientific literature, a hyperosmolarity-sensing transcription factor, and CREB3L1 are both involved in vasopressin synthesis during hyperosmolarity.

Based on this data, we can hypothesize that hyperosmolarity might trigger a mechanism involving CREB3L1 in the thyroid gland that would stimulate the synthesis of thyroid hormones without the need for TSH or with a reduced requirement for it.

Next, we will explore how NFAT5 may also play a role in the signaling of the synthesis of thyroid hormones by allowing the thyroid to uptake a specific nutrient called inositol, which also happens to belong to an interesting class of compounds, osmolytes.

NFAT5, inositol and the thyroid

The following study describes how inositol (referred to as MYO) is involved in the signaling of thyroid hormones synthesis, and how it could be crucial to certain thyroid issues, like Hashimoto’s disease or hypothyroidism.

Therefore, it is not surprising that impaired MYO homeostasis correlate with a wide variety of conditions, including thyroid disorders, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), fertility disorders, diabetes, metabolic, and neurological disorders.

[…] Therefore, MYO exerts a crucial role in thyroid physiology, by its function in TSH regulation of iodination and by an increased sensitivity of thyrocytes to TSH. Metabolomic investigations confirmed such evidence, indicating that MYO demand is higher in hypothyroid patients than in healthy subjects, making MYO very appealing as a molecule to increase iodine availability counteracting thyroid dysfunctions.

The Role of Inositol in Thyroid Physiology and in Subclinical Hypothyroidism Management

Inositol is necessary for the signaling involved in the synthesis of thyroid hormones. This signal induces iodine organification (also called “iodination”), which initiates thyroid hormone synthesis.

An interesting fact is that NFAT5 may be involved in inositol uptake in the thyroid. This transcription factor is known to counter osmotic stress by upregulating proteins, called "transporters", that facilitate the uptake of osmolytes, including inositol:

Functionally, NFAT5 activates a large number of target genes implicated in osmoprotective responses, including those encoding aldose reductase, the betaine transporter, and the inositol transporter. With its wide range of cell type and tissue expression patterns, NFAT5 plays a prominent role in restoring intracellular osmotic balance under hypertonic conditions.

Therefore, by NFAT5 activation and inositol uptake to make up for osmotic stress, hyperosmolarity could also facilitate proper TSH signaling and iodine organification.

Given these theoretical considerations, the next section will review some experimental data involving water restriction, vasopressin injections or deuterium depletion on TSH and thyroid hormones levels.

Water restriction and vasopressin effects on the thyroid

In the following study, a model of hypothyroidism was induced in rats by giving them an inhibitor of the TPO enzyme, which is involved in iodine organification in the thyroid. Water restriction for two days seemed to increase the concentration of T3 in the blood, almost bringing it back to the level found in the control group (referred to as "euthyroid rats" in the graph).

Vasopressin and oxytocin release and the thyroid function

These results indicate that water restriction may increase T3 blood levels, possibly through the mechanisms proposed in previous sections, namely increased inositol uptake and activation of CREB3L1.

Interestingly, the paper's other data shows that blood vasopressin levels did not significantly increase in the hypothyroid group during water restriction, in comparison to the euthyroid group:

The following paper examines the effect of vasopressin injections on the thyroid of rabbits and reports an interesting finding:

It is concluded that vasopressin exerts a direct action on the thyroid gland. This action is identical with that exerted by appropriate doses of TSH in its time relations, and in the nature of the compounds released from the gland (inorganic iodide and the iodothyronines, but not the iodotyrosines).

Vasopressin and thyroid function in the rabbit

The authors conclude that in the rabbit, vasopressin tends to feature the same effect than TSH on the thyroid in terms of thyroid hormone secretion.

Thus, while the previous publication found that water restriction seemed to induce T3 synthesis in an hypothyroid rat model without an increase in vasopressin levels in the blood, this one found that vasopressin injections had the same effect in rabbits.

It is important to keep in mind that increasing vasopressin levels through injections of it, at constant water consumption levels, would result in a decrease in blood osmolarity. Inversely, water restriction without an increase in vasopressin levels (as in the study on rats) might mean an higher blood osmolarity than if vasopressin had “normally” increased.

Thus, there might exist a complementary effect between hyperosmolarity and vasopressin on the thyroid during water restriction.

Now we will see the effect of deuterium (an isotope of hydrogen connected to water consumption) depletion and water restriction on TSH levels.

Deuterium depleted water and water restriction impact on TSH

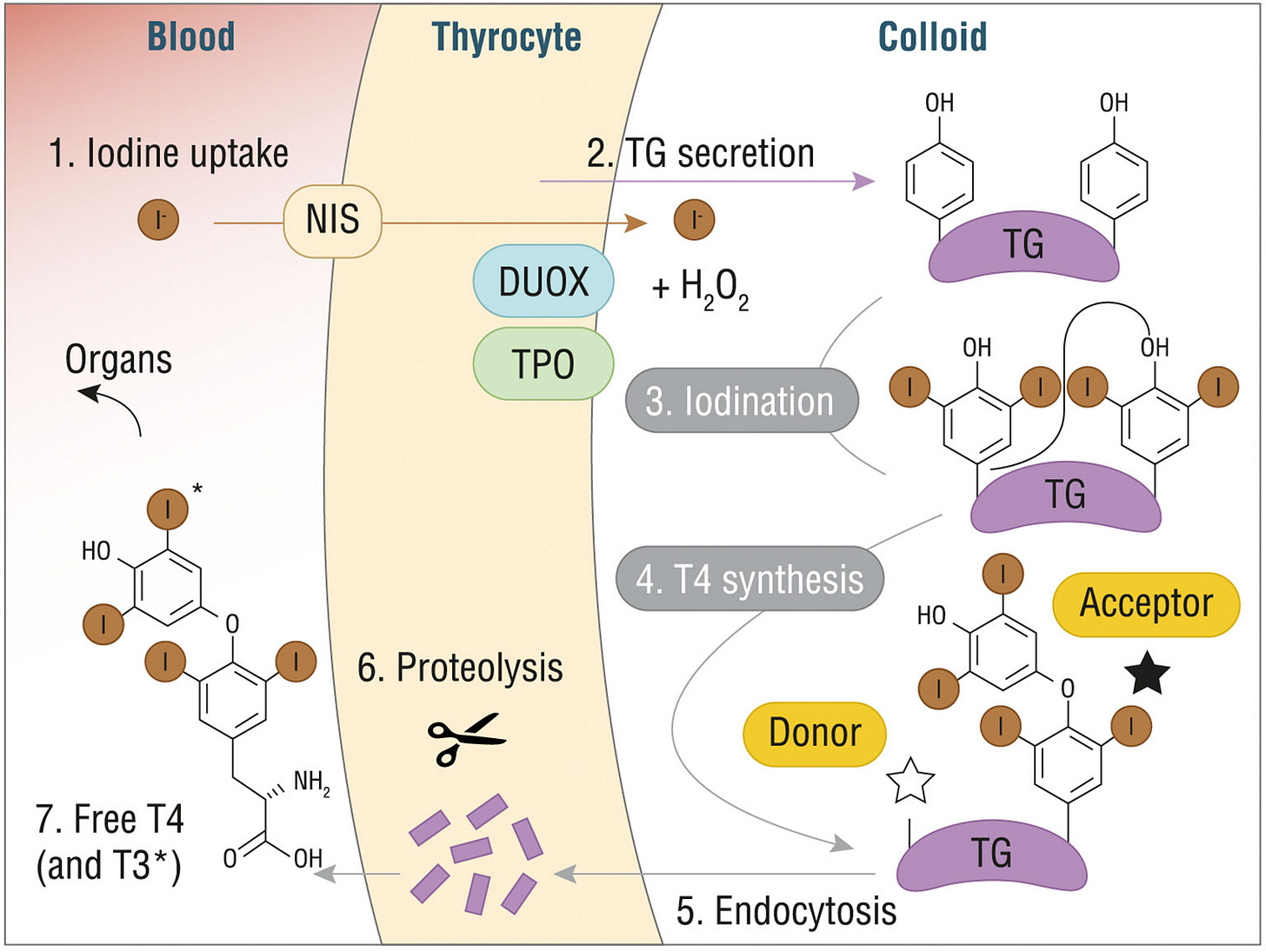

In this experiment, groups of rats were given either water with very high concentrations of deuterium (about 3500 times more than control), or deuterium depleted water (a concentration divided by about 15).

In the two groups, the TSH levels were quite reduced as it was more than halved with respect to the control group, while free T4 and free T3 levels were reduced a bit too:

Response of Pituitary—Thyroid Axis to a Short-Term Shift in Deuterium Content in the Body

Hence, something seemed to sense the deuterium concentration and, as it was lower (or higher) than the normal deuterium concentration, lead to a decrease in TSH synthesis. Regarding the lower concentration of deuterium, it can be hypothesized that the deuterium concentration of the blood might be monitored as a proxy for water consumption

Given that deuterium-depleted water was used instead of water restriction, the rats potentially consumed the same amount of water, therefore, no hyperosmolarity must have been induced. There was no significant increase in T4 and T3 levels over the control group values. However, there might have been a boost in thyroid hormones synthesis as their levels were almost equal to that of the control group, while the TSH levels of the rats were only one fourth of the control group's TSH levels.

In the following study, rats were subjected to water restriction by limiting the time they had access to water. It was observed that their TSH levels were lowered during it.

Water restricted rats were allowed to drink between 9.00 and 9.30 a.m. only. […] In contrast, neither acute nor chronic water restriction altered the qualitative patterns of circadian GH and TSH rhythms although both treatments depressed the secretion of the two hormones, the depression being greater in chronic than in acute water restricted rats.

Finally, we’ll see how the thyroid system interacts with bile acids which are themselves connected to water homeostasis.

TSH, bile acids and water homeostasis

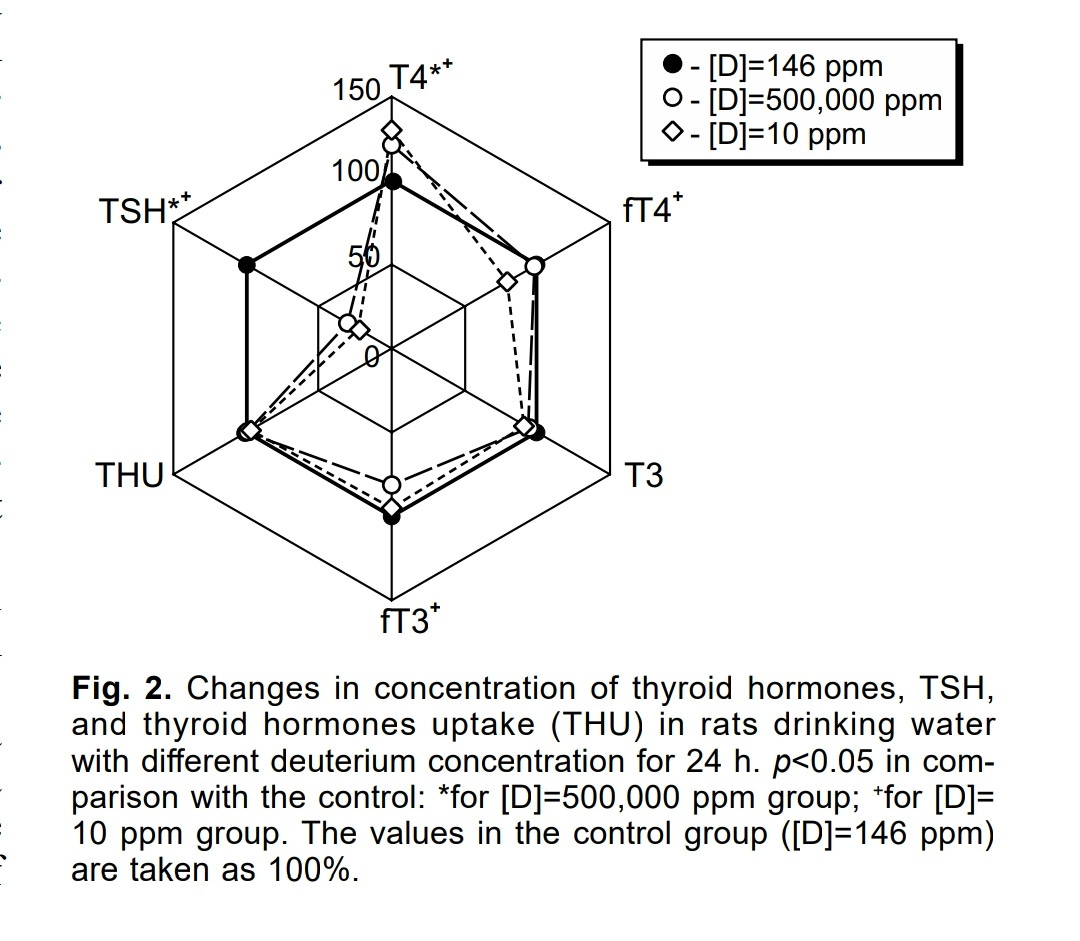

In the following publication, a bi-directional link between the TSH hormone and bile acids synthesis and circulation in the blood is suggested:

The negative association between serum bile salts and TSH uncovered in the present study raises the intriguing question whether bile salts may actually control TSH levels. Pituitary release of TSH is subject to negative feedback control by locally produced T3. This requires the action of one of three iodothyronine deiodinases encoded by the DIO1–3 genes. These enzymes catalyze activation and inactivation of THs. DIO2 has previously been identified as a bile salt-induced gene in brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, and catalyzes formation of active T3. The G-protein coupled receptor TGR5 (a.k.a. GPBAR1) confers induction of DIO2 by bile salts. This plasma membrane bile salt receptor is broadly expressed, including in the hypothalamus and pituitary. If bile salt-inducibility of DIO2 is maintained in these tissues, bile salts may regulate the negative feedback control of release of hypothalamic TSH-releasing hormone (TRH) and pituitary TSH. TGR5 may thus link circulating bile salts to peripheral TH/TSH action, with elevation of bile salts resulting in diminished TSH levels and vice versa, as is observed in the human study of Song et al..

Pituitary TSH controls bile salt synthesis

TSH has been found to control the production of bile acids in the liver. Higher TSH levels means less bile acids produced as TSH inhibits the enzyme CYP7A1 that converts cholesterol into bile acids.

Conversely, bile acids, through their potential activation of deiodinase in cells of the pituitary via the TGR5 receptor, could decrease the release of TSH in the blood. Indeed, a local increase of the T3 levels in the pituitary may inhibit TSH release as a negative feedback mechanism seems to exist.

As mentioned above, bile acids, via the TGR5 receptor when it is present on a cell’s surface, can upregulate the deiodinase enzyme D2 in the cell, inducing the conversion of T4 to T3:

This indicates that BAs might be able to function beyond the control of BA homeostasis as general metabolic integrators. Here we show that the administration of BAs to mice increases energy expenditure in brown adipose tissue, preventing obesity and resistance to insulin. This novel metabolic effect of BAs is critically dependent on induction of the cyclic-AMP-dependent thyroid hormone activating enzyme type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase (D2) because it is lost in D2-/- mice. Treatment of brown adipocytes and human skeletal myocytes with BA increases D2 activity and oxygen consumption. These effects are independent of FXR-α, and instead are mediated by increased cAMP production that stems from the binding of BAs with the G-protein-coupled receptor TGR5. In both rodents and humans, the most thermogenically important tissues are specifically targeted by this mechanism because they coexpress D2 and TGR5. The BA–TGR5–cAMP–D2 signalling pathway is therefore a crucial mechanism for fine-tuning energy homeostasis that can be targeted to improve metabolic control.

Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation

As a consequence, the concerned tissues have an increased metabolic rate. This result has been found in brown adipose tissues (fat cells being able to burn fat to generate heat) and muscle cells, and is hypothesized to happen in the pituitary in the previous paper. This means that the metabolic rate is increased by local (in the tissue) deiodination of T4 to T3 with help of bile acids that circulate in the blood. Moreover, this locally produced T3 might contribute to the systemic T3 levels as discussed in this paper:

The deiodinase signaling pathways in peripheral tissues constitute a major determinant of plasma T3 level, since all T3 generated in the cytoplasm eventually exits the cell, unless of course it is metabolized.

Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action

Paradoxically and according to this mechanism, a decrease in TSH levels might produce an increase in blood’s bile acids concentration, which would induce the activation of the deiodinase enzyme D2 in peripheral tissues and could contribute to a systemic T3 levels increase.

Bile acids and water homeostasis

Finally, bile acids seem to be related to water homeostasis as they can upregulate the aquaporin AQP2 of the kidneys, through the TGR5 receptor again, so as to help water conservation:

TGR5 stimulation increases renal AQP2 expression and improves impaired urinary concentration in lithium-induced NDI. TGR5 is thus involved in regulating water metabolism in the kidney.

Bile Acid G Protein-Coupled Membrane Receptor TGR5 Modulates Aquaporin 2-Mediated Water Homeostasis

FXR, another bile acid receptor is also involved in water homeostasis in the kidneys.

It would be logical that in a state of water restriction, bile synthesis and flow would be increased in order to these mechanisms to be properly functioning.

Vasopressin might play a potential role as it seems that the vasopressin receptor called V1a could be able to stimulate bile flow and secretion:

Desmopressin increased bile flow, secretion of total cholates like amino acids conjugated, while diminished free bile acids content. Secreted bile volume and conjugated bile acids content were reduced in V1a receptors antagonist+desmopressin-treated rats. In contrast, free bile acids content was more than the results in desmopressin-treated rats. Desmopressin at concentrations nearly equal to physiological concentrations of natural hormone in blood shows its choleretic effect. Antagonist of V1a vasopressin receptors modulates desmopressin action. This certifies the role of these receptors in the action of desmopressin on different processes of bile formation.

Desmopressin stimulates bile secretion in anesthetized rats

Conclusion

The connections between water homeostasis, hyperosmolarity and the thyroid system are listed below:

There exist theoretical arguments allowing us to hypothesize that hyperosmolarity, induced by water restriction for example, could facilitate the synthesis of thyroid hormones while potentially lowering the requirement for TSH stimulation.

Rats (with an animal model of hypothyroidism) put under water restriction got an increase in their T3 levels, bringing them almost back to the control group’s levels.

It was found that, in rabbits, vasopressin itself seems to play a role similar to TSH regarding thyroid hormone synthesis.

Two studies on rats found that water restriction or deuterium depleted water (which might be interpreted by the body as water restriction) tend to lower TSH levels.

Finally, bile acids could be related both to the TSH and metabolic rate of tissues involved in thermogenesis, but are also related to water homeostasis as the bile acid TGR5 receptor (along with the FXR transcription factor) is involved in kidneys’ function. From this data, we can hypothesize that a TSH decrease itself could boost T3 systemic levels as it might increase bile acids synthesis and thus peripheral deiodinase enzymes.

Thus, water restriction (or deuterium depletion) could lead to a TSH decrease while keeping thyroid hormones levels maintained or increased. The TSH decrease could be explained by an increase in vasopressin, which could play the role of a TSH surrogate and stimulate bile acids synthesis and thus the conversion of T4 to T3 in peripheral tissues.

Another explanation could be that hyperosmolarity itself, by activating the NFAT5 transcription factor which would upregulate the uptake of inositol by the thyroid, or activating the CREB3L1 transcription factor, would increase the sensitivity of the thyroid gland to TSH and optimize thyroid hormones output.

Upping intake of inositol, selenium and intermittently restricting water intake to achieve hyperosmolarity may improve the function of the thyroid system.

Super interesting compilation of scientific finds. Thanks!

Albeit suspected this connection, between thyroid health and kidney-antideuretic function, never thought of it formally. When I started 'peating' and restricting my plain water intake, one of the 1st things I've noticed are better antideuretic function..

Re: bile acid and thyroid connection

Now it becomes cleared to me, why taurine, which is big bile promoter, acts so well on the thyroid health and metabolism, in general.

Hence, I'd add taurine to the list of recommendations in your last sentence. This way you 'throw in' into the mix something for the bile.

Will read up more on inositol too,

P.S. Got to your substack from your link on RPF (and glad I did!). Cheers from lejeboca ;-)

Absolutely fascinating. Thank you so much for this. This is the first article I found on your site but I'm planning to dig in and enjoy others now.